Hybrid Models of Ethics in AI

Hybrid approaches are a blend of top-down and bottom-up methodologies for AI ethics. In this article, we dive deeper into hybrid models of ethics for AI and give two examples of how they can be applied. We will explore why hybrid models are more hopeful than top-down or bottom-up methodologies on their own for ethical AI development, and ask questions regarding what problems they may face in the future.

First, we will delve into MIT’s moral machine as one example of hybrid ethics being taught to systems for self-driving vehicles. Then we will explore a study of hybrid ethics being trained on ethical medical situations.

We conclude this exploration by further examining the meaning and construct of hybrid ethics for AI while linking the case studies as an exercise in exploring the potential positive and negative impacts of hybrid ethical AI approaches.

How do we define a hybrid model of ethics for AI?

A hybrid model of top-down and bottom-up ethics for AI has a base of rules or instructions, but then also is fed data to learn from. Real-world human ethics are complex, and a hybrid approach may minimize the limitations of top-down and bottom-up approaches to machine ethics, combining rule-based cognition and protracted ethical learning. (Suresh et al., 2014)

Hybrid AI combines the most desirable aspects of bottom-up, such as neural networks, and top-down also referred to as symbiotic AI. When huge data sets are combined, neural networks are allowed to extract patterns. Then, information can be manipulated and retrieved by rule-based systems utilizing algorithms to understand symbols. (Nataraj et al., 2021) Research has observed the complementary strengths and weaknesses of bottom-up and top-down strategies. Recently, a hybrid program synthesis approach has been developed, improving top-down interference by utilizing bottom-up analysis for web data extraction. (Raza et al., 2021) When we apply this to ethics and values, ethical concerns that arise from outside of the entity are emphasized by top-down approaches, and the cultivation of implicit values arising from within the entity is addressed by bottom-up approaches.

MIT’s Moral Machine as a Hybrid Model for AI Ethics

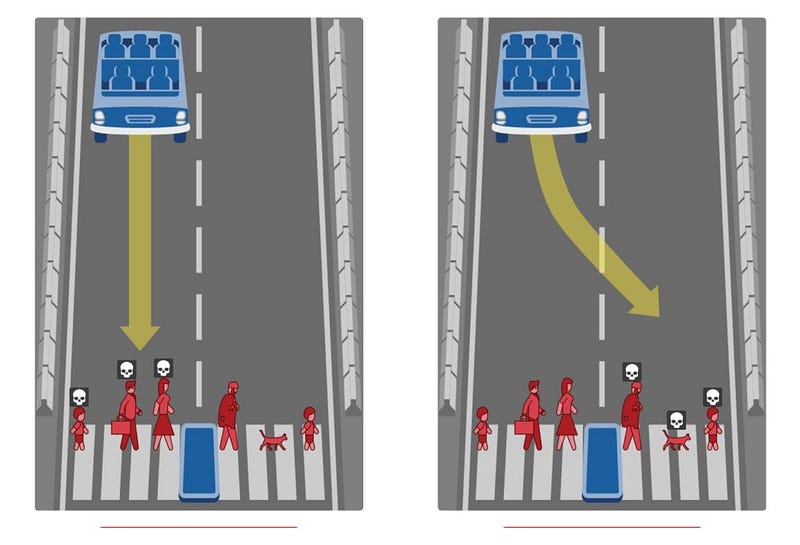

MIT’s Moral Machine is a hybrid model of AI ethics. It is an online judgment platform geared toward citizens from around the world portraying the moral dilemmas of unavoidable accidents involving automated vehicles (AVs), and what choices individuals would assign for them to respond. Examples include whether to spare humans versus pets or pedestrians versus passengers, with many factors to consider such as gender, age, fitness, and social status. The Moral Machine collects this data and maps it regionally to compare homogeneous vectors of moral preferences in order to provide data to engineers and policymakers in the development of AVs and to improve trust in AI. (Awad et al., 2018) This research is a hybrid of top-down and bottom-up because it collects data from citizens in a bottom-up manner, while also considering top-down morals, principles, and fundamental rules of driving.

Example from the

where we see the choice between hitting the group on the left or the right. Which would you choose?

However, if the data shows that most people prefer to spare children over a single older adult, would it then become more dangerous for an elderly individual to walk around alone? What if we were to see a series of crashes to avoid groups of school children but run over an unsuspecting lone elder? The situations they give in the simulations are to choose between two scenarios, each resulting in unavoidable death. These decisions are made from the comfort of one’s home and maybe made differently if in the heat of the moment. Is it better to collect these decisions in this way, vs observing what people do in real scenarios? Where would a researcher acquire this data for training purposes? Would police accident reports or insurance claims data offer insights?

It is useful to collect this data, however, it must also be viewed alongside other considerations. Real-life scenarios will not always be so black and white. I personally despise the ‘trolley problem’ and emulations of it, which make us choose who deserves to live and who will be sacrificed. We may think we would hit one person to save a group of people, but who would want to be truly making that decision? It feels awful to be in this position, however, this is the point behind the simulation. In order to build trust in machines, ordinary people need to make these decisions to better understand their complexity and ramifications. Considering the MIT Moral Machine has collected data from over 40 million people, does this take the responsibility away from a single individual?

What they found was that although there are differences across countries and sections of the globe, there is a general preference to spare human lives over animals, spare more lives over fewer, and spare younger lives over older. Looking at the world in sections, there are trends that emerged in the West versus South versus East. For instance, in the Eastern cluster, there was more of a preference for sparing the law-abiding over the law-breaking, and in the Southern cluster, there were more tendencies toward sparing women over men. Policymakers should note that differences abound between individualistic versus collectivist cultures. Individualistic cultures value sparing the many and the young, whereas collectivist cultures value the lives of elders. How these preferences will be understood and considered by policymakers is yet to be determined. (Awad et al., 2018)

Hybrid Ethics for Moral Medical Machines

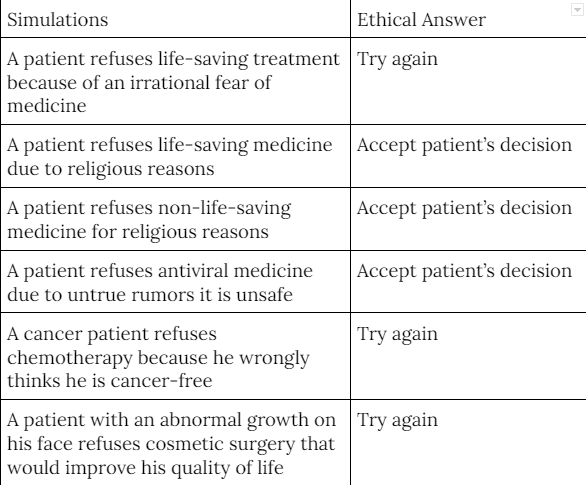

The second example we will examine is an experiment that was done using six simulations to test a moral machine that would emulate the decisions of an ethical medical practitioner in specific situations, such as with a patient refusing life-saving treatment. The decisions were based on ethics defined by Buchanan and Brock (1989), and the moral machine would copy the actions of the medical professional based on each circumstance.

(van Rysewyk & Pontier, 2014)

It appears straightforward to run an experiment based on a theoretical case study and tell the machine what a human would do, and then the machine can simply copy the same actions. However, how many simulations would it need to be trained on before it could be trusted to act on its own in real-life situations?

We may indeed come across patients refusing life-saving medication, whether due to irrational fear or religion or a host of other reasons. Additional outlying considerations include whether relatives or primary caregivers have opposing opinions to the treatment. Additionally, if there are financial constraints, there could be other complications that make each situation unique. A human medical professional would be able to consider all factors involved and approach each case anew. A moral machine would be basing predictions on past data, which may or may not be sufficient to address the unique needs of each real-life scenario.

Theoretically, the machine would learn more and more over time, andpotentially even perform better at ethical dilemmas than a human agent. However, this experiment with six basic simulations doesn’t give the utmost confidence that we are getting there quickly. Nonetheless, it gives us a good example of hybrid ethics for AI in action, since it is acting within a rule-based system as well as learning from case-based reasoning.

In these cases, they are balancing the benevolence, non-malevolence, and autonomy of the patient. (Pontier & Hoorn, 2012) (van Rysewyk & Pontier, 2014) Another paper on this topic added a fourth consideration which is Justice. They went on to describe a medical version of the trolley problem, where five people need organ transplants and one person is in a coma and has all the organs that the five people need to live. Would you kill one to save five? (Pontier et al., 2012)

Conclusion

Could a hybrid of top-down and bottom-up methodologies be the best application for ethical AI systems? Perhaps, however, we must be aware of the challenges it presents. We must examine the problems posed by hybrid approaches when meshing a combination of diverse philosophies and dissimilar architectures. (Allen et al., 2005) However, many agree that a hybridof top-down and bottom-up would be the most effective model for ethical AI development. Simultaneously, we need to question the ethics of people, both as the producers and consumers of technology, whilst we assess morality in AI.

Additionally, while hybrid systems which lack effective or advanced cognitive faculties will appear to be functional across many domains, it is essential to recognize times when additional capabilities will be required. (Allen and Wallach, 2005)

Regarding MIT’s Moral Machine, it is interesting to collect this data in service of creating more ethical driverless vehicles and to promote more trust in them from the public, however, the usefulness of it is yet to be proven. (Rahwan, 2017) AVs will be a part of all of our lives on a daily basis, so it is valuable to know that public opinions are being considered.

In the field of medicine, there is a broader sense of agreement on ethics than in something like business ethics, however, healthcare in the United States is a business, which causes decisions for and against the treatment of a patient to get very ethically blurred.

It will be vital as we move forward to identify when additional capabilities will be necessary, however functional hybrid systems may be across a variety of domains, even with limited cognitive facilities. (Allen and Wallach, 2005) AI development must be something that we keep a close eye on as it learns and adapts, we must note where it can thrive, and where a human is irreplaceable.

You can stay up to date with Accel.AI; workshops, research, and social impact initiatives through our website, mailing list, meetup group, Twitter, and Facebook.

Join us in driving #AI for #SocialImpact initiatives around the world!

If you enjoyed reading this, you could contribute good vibes (and help more people discover this post and our community) by hitting the 👏 below — it means a lot!

References

Allen, C., Smit, I., & Wallach, W. (2005). Artificial Morality: Top-down, Bottom-up, and Hybrid Approaches. Ethics and Information Technology, 7(3), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-006-0004-4

Awad, E., Dsouza, S., Kim, R., Schulz, J., Henrich, J., Shariff, A., Bonnefon, J. F., & Rahwan, I. (2018). The Moral Machine experiment. Nature, 563(7729), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0637-6

Buchanan, A. and B. D. (2004). Deciding for others: The Ethics of Surrogate Decision making. Cambridge University Press.

Pontier, M. A., & Hoorn, J. F. (2012). Toward machines that behave ethically better than humans do. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society.

Pontier, M. A., Widdershoven, G. A. M., & Hoorn, J. F. (n.d.). Moral Coppélia-Combining Ratio with Affect in Ethical Reasoning.

Rahwan, I. (2018). Society-in-the-loop: programming the algorithmic social contract. Ethics and Information Technology, 20(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-017-9430-8

Suresh, T., Assegie, T. A., Rajkumar, S., & Komal Kumar, N. (2022). A hybrid approach to medical decision-making: diagnosis of heart disease with machine-learning model. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), 12(2), 1831. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijece.v12i2.pp1831-1838

Vachnadze, G. (2021). Reinforcement learning: Bottom-up programming for ethical machines. Marten Kaas. Meium.

van Rysewyk, S. P., & Pontier, M. (2015). A Hybrid Bottom-Up and Top-Down Approach to Machine Medical Ethics: Theory and Data (pp. 93–110). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08108-3_7

Wallach, W., Allen, C., & Smit, I. (2020). Machine morality: bottom-up and top-down approaches for modelling human moral faculties. In Machine Ethics and Robot Ethics (pp. 249–266). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003074991-23